1948 War. Lolek, a young Holocaust survivor arrives in Israel and thrown in the middle of the desert. A stranger to the language and the new identity he is given, he is assigned in an isolated post under a brutal commander and the burning sun. Afflicted by homesickness and the heat, he sets out to look for some shade.

Synopsis

1948 War. Lolek, a young Holocaust survivor arrives in Israel and thrown in the middle of the desert. A stranger to the language and the new identity he is given, he is assigned in an isolated post under a brutal commander and the burning sun. Afflicted by homesickness and the heat, he sets out to look for some shade.

Festivals

- Thalia Kino, Dresden, Germany, 2009

- Philadelphia Jewish Film Festival, USA, 2010

- Dresden Jewish Film & Music Week, Germany, 2009

- 4th Forum of Israeli Cinema in Russia, 2009

Press & Links:

Director Dani Rosenberg’s movie, “Beit Avi” — literally, “My Father’s House”; known in English as “Homeland” — is a 40-minute drama about a young Holocaust

refugee who comes to Israel in 1948. It premiered at the Jerusalem International Film Festival last year. Since then, it has been screened at almost a dozen festivals round the world and has garnered strong reviews for the daring questions it raises, which strike at the core of Israel’s identity.

In the film, the refugee, Lolek (Itay Tiran), comes to Israel, hoping to find his sweetheart in Haifa. Instead, he is immediately conscripted into the army. Few people know about this chapter of Israel’s history, when the refugees of the Holocaust were forced to serve in the Israeli military, despite the fact that they knew no Hebrew and understood little about the conflict with the Arabs. In an interview with the Forward, Rosenberg said he aimed to do more than just tell about this controversial practice.

“I also wanted to show how Israel in general denigrated everything that the Holocaust survivors represented, and how important it is for us to learn their history in order to understand who we are today,” Rosenberg said. “That’s why I felt the film had to be in Yiddish. By Yiddish, I don’t just mean the language, but also the culture which the Israeli government and society tried to erase.”

For the entire review by Rukhl Schaechter/The Jewish Forward, April, 2009,

check: www.forward.com/articles/104647/

"Homeland offers not only a revisionist account of Israeli history, but of Israeli cinema as well. More than any other Israeli director, Dani Rosenberg explores the price paid by the individual for the demands put on them by the Zionist endeavor. Other Israeli filmmakers, no matter how critical of the Zionist project and of Israeli society, tended to mitigate the stress of this demand by placing their protagonists within the context of a collective-commonly represented by a small group of people or a family-and in doing so, submitted their anguish to its impersonal logic. By placing this community outside of the film's frame and by rendering the significance of the struggle against its demands uncertain, Homeland turns that anguish into a challenge to talk about Israeli history."

For the entire review by Prof. Shai Ginsburg/Duke University,

check: http://www.jewcy.com/post/selfdestructive_logic_militarism

Land of our Forefathershttp://stevie.blogli.co.il/archives/210

The opening of Dani Rosenberg's new film "Homeland" is somewhat reminiscent of Herbert Klein's 1947 film "My Father's House" – a jeep loaded with new immigrants from Europe on the roads of Israel, thru the desert, taking them to their new future. But that is about all those two films have in common. Klein's film is a pretty standard Zionist party line ….[in this film] in the middle in the desert, with nothing around – and certainly not Haifa which is where the character wants to go – he has no choice but to go up the hill to the outpost.

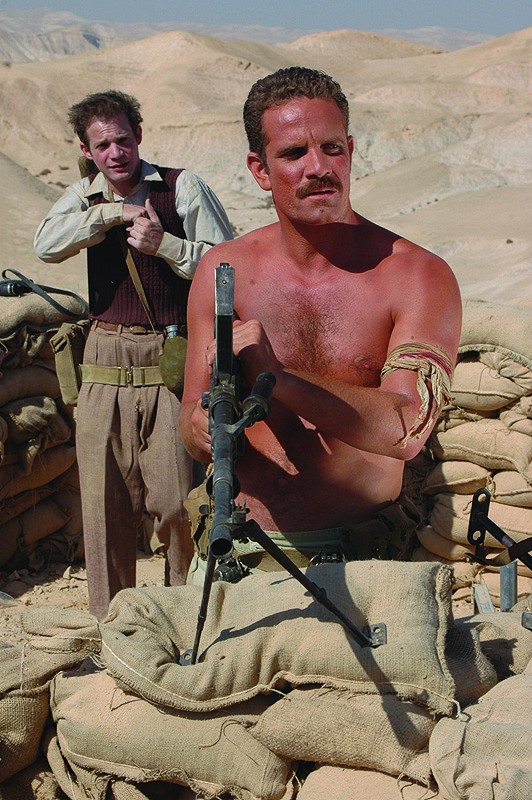

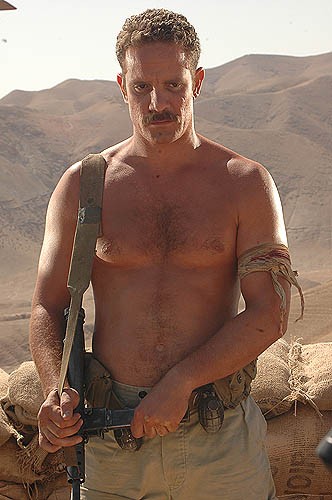

It is here that he meets his commarade and commander, who was once a pale survivor like himself, and is now a tanned "Sabra"- muscular, mustached and armed. He says to the new arrival "soon we will not even be able to tell where you came from". And this is the point from which our hero begins his journey to become an Israeli.

From brand new to well-worn, from wide-eyed to well versed, from fleeing to being an authority. ..In this country is it even possible to remember from where you came?

This is a political film about power, the military, occupation and victimhood. And all of this is happening with a war that is out of view, and there is no shelter from the blaring sun - or the facts on the ground.

This is a protest film about erasing the past; roots, culture and memory. One could say this is also a personal film about private loss and belonging. It is a film about longing and changes and memory – personal memory and not collective memory, just what is etched in your own remembrances.

This might sound dense, but these are just some thoughts about a complex screenplay that raises many issues while not making the viewing experience too crowded. The film flows, fascinating and gripping and is helped greatly by excellent acting (especially by Itai Tiran), beautiful cinematography and precise editing.

The Post-Zionist Lawrence of Arabia

after watching Dani Rosenberg's new film "Homeland", our critic has decided to take Yiddish classes

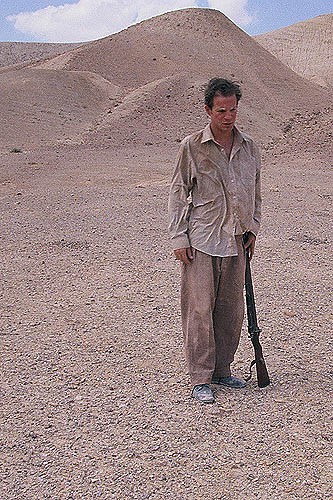

Faces of refugees in the dark. They rock back and forth in their place. They are in a truck. Sudden stop. We see that the truck has stopped in the desert in the middle of nowhere. The natural light is blinding. One of the refugees is thrown off the truck – he is pale and wearing a sweater (Itai Tiran). He is given a rifle and sworn in as a soldier in the IDF. Thus begins Dani Rosenberg's Yiddish speaking film which is now showing at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque.

The film focuses on a simple yet abstract point – two figures and a flag on a hill; one of them is a survivor of Auschwitz who wants to find his love in Haifa, and the other a "new Jew" (Mikki Leon) – the Israeli soldier. The movie intertwines the absurd with contemporary debate that are echoing in current discussions of Zionist cinema. The flashes of bright light in the film relate directly to a series of photographs by Helmar Larsky – while the title of the film conveys the history of Israeli film since the title is borrowed from a 1947 film directed by American Herbert Klein.

……

The film is filled with tensions – between the characters, between the Yiddish language and the desert landscape, between the Israeli and the Jew, the refugee and the soldier, the past and the present, between ideals and reality. The tension between the identity of an Israeli and that of a Jew is presented as a moral tension where in order to become Israeli the refugee must learn to kill in order to become Israeli.

The film is merciless in its direct approach and brutal story line….The frank style of direction as well as the revealing cinematography of Dudu Stusmiester presents the main character of the film – the hot Israeli sun. While the soldier is abusing the new immigrant, the Holocaust survivor, the sun is beating down. The desert sun is supposed to tan the survivor and blur the number tattooed on his arm. The sun plays a central role in this film, much like in "The Stranger" by Camus.

Yehoshua Simon, City Mouse –Tel Aviv, September 11, 2008

http://www.mouse.co.il/CM.articles_item,519,209,27696,.aspx

A Yiddishe BubeeItay Tiran is an old Yiddish actor in the wild-west of Israel. Romi Mikolinski saw Dani Rosenberg’s new film “Homeland” and was impressed.

“Homeland”, Dani Rosenberg’s short Yiddish language film deals with a painful topic – the inscription of refugees fleeing Europe at the end of World War II into the Israeli military. Even now it is not clear how many were forcibly conscripted into the Zionist state’s army without knowing a word of Hebrew, who was fighting whom and where they were located. Rosenberg’s character Lolek portrays with his body, with his broken Hebrew and above all with his paleness the utter confusion that those refugees experienced the authenticity of the war in Europe much more than the conflict in Palestine. Rosenberg stubbornly insists on bringing up issues that were all but forgotten in the construction of a new ethos for a fighting nation. Issues that are uncomfortable now just as they were in the past. It is easier to deny things. First and foremost “Homeland” is about the forced inscription – but the film also forces the audience to confront the issue of abandoned Arab villages and the issue of Palestinian refugees. Suffering belongs to all the film seems to suggest – to the long-time residents of the land (Jews and Arabs alike) and to those newcomers as well.

“Homeland” is a short film of less than 40 minutes and it is hard to compare it to other films. The experience of watching the film is unusual and not only because most of the film is in Yiddish. It is an intense viewing experience. It sometimes feels like the use of the language is not only authentic – but also underscores Lolek’s isolation and loneliness. Most of the film takes place in a remote out-post over looking the dessert where Lolek meets Mintz (Mikki Leon) – who, like Lolek is a Holocaust survivor with a number on his arm, who terrorizes his stunned charge. The contrast between the two is marked and is first and foremost indicated by their physical differences. Unlike Mintz who has already shed all the trapping of his Diaspora self only to become the poster-boy for the new Israeli – Lolek’s inadequate body is a stumbling block on his way to becoming a “Sabra”. The homo- erotic tension between the two men and the master-slave relationship they conduct only increases as the weaker Lolek refuses to go along with Mintz’s demands –and by extension those of the whole Yishuv (pre-State community) – refuses to loose his previous identity, to grow stronger. “A few more days in the sun and no one will be able to tell where you are from” Mintz goads him on and encourages him to develop muscles and a tan. “You have more work” he demands in his dictatorial way.

Rosenberg adeptly captures the fearful atmosphere of that mad time, even as his cinematic language tends to be somewhat simplistic at times. His use of symbols and foreshadowing, like the use of certain camera movements, is meant to convey the fear of the characters, their unstable nature – though these are too simplistic and obvious especially paired with the amazing natural landscape which is at once claustrophobic and open. The power of the film derives from the excellent performances of the two main actors. Tiran not only transforms into Lolek, but also is able to become before our very eyes into an ageless immigrant: at once an old Yiddish comic with terrific facial expressions. Leon gives a precise performance which conveys a man on the brink of collapse. He is powerful yet vulnerable, torn between two countries and experiencing the War for Israeli Independence as if it was the Wild West. The tan and muscular Mintz is perhaps the personification of the Zionist pioneers, but he is also the proof of the price one has to pay to erase a previous identity. “Homeland” offers a brave and unique interpretation not only of the pre-State settlement, but also of what is involved in the building of an ethos upon we were all raised. Rosenberg does not hesitate to criticize those notions and to show what has been lost along the way. He does so with the choice of Yiddish, or by exposing the abandoned Arab villages. By creating a connection between two abandoned cultures that of the Palestinians and that of the Eastern European Jews.Romi Mikolinski, www.walla.co.il, September 9th, 2008

Yiddish is revived in the film Homeland

Who says Yiddish is dead? It is true that you don't hear it much and it is mostly spoken by octogenarians – but at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque and other cinematheques around the country, a new film with two young actors in entirely in Yiddish and they do such a good job that it is hard to believe that Yiddish is not their mother tongue.

I am talking about Itai Tiran and Miki Leon who for 40 minutes manage very nicely to convey real emotions, conflicts, some criticism about the fundamental nature of Zionism, about Israelis and about human beings in general.

Homeland tells the story of Lolek, a young Holocaust survivor (played by Itai Tiran) who arrives in Israel in 1948 wanting to get to Haifa to meet his girlfriend Nina. Instead he is sent to a remote outpost in the Negev dessert.

It is at this outpost that he meets the man who will become his commander, his close friend, and possibly the last person he will ever see.

Their complicated relationship (but very basic), the nightmares from the Camps and the hot sun – oh the Israeli sun which brings us so much fame and tourists – turns out to be the real enemy of these two.

It is true that the film is only 40 minutes long, but you get the sense of a full film, perhaps not perfect, but full. Two men at one outpost – what could happen? As it turns out, quite a lot and nothing at all. The process is mainly internal and both actors do a great job. The cinematography is professional and serves the screenplay and the demands of the director almost perfectly. The music by Avi Binyamin only completes the picture and turns this into one of the more professional films to come out of the student film category.www.seret.co.il, Reviewed by Alon Rosenberg, August, 2008

New film follows Holocaust refugees-turned-soldiersVeteran Israeli actor Itay Tiran is starring in a new movie opening this week at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque, in the language of his grandparents, Yiddish.

"Beit Avi", or "Homeland", tells the tale of two refugees from the Holocaust who find themselves posted on a remote desert hilltop during Israel's 1948 War of Independence.

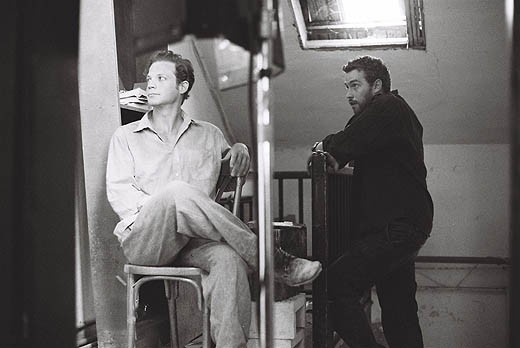

Filmmaker Dani Rosenberg wrote the movie in Hebrew, and then made the unusual decision to have the dialogue spoken in Yiddish, a feat that required he and Tiran spend months studying the language. For the filmmakers, filming in Yiddish gave the movie an air of realism they say it would've lacked otherwise.

The movie's Yiddish dialogue and treatment of the time passed the test of a serious critic, Rosenberg's grandmother.

www.haaretz.com; August 21, 2008

Refugee ReduxTwo European Jews - Holocaust refugees swiftly transformed into Israeli soldiers - are roasting in the sun on a remote desert hill at the height of the 1948 War of Independence. They can only communicate with each other in Yiddish, and it seems as if they are the only two people left in the world. The Nazis remain in Europe and in their nightmares, the Palestinians have already been driven out of nearby villages, and even the war in which they are participating is only a faint echo on the army transmitter. It is at the heart of this ahistorical moment that Dani Rosenberg's unusual new film "Beit avi" ("Homeland") is planted. Starring Miki Leon and Itay Tiran, it opens next week at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque.

The two heroes, Mintz and Lolek, are opposites. Mintz (Leon), tanned and muscular, sporting a mustache, denies his European past and reinvents himself as a Hebrew-speaking Israeli soldier. Lolek (Tiran), bony and pale, is dragged into the war by mistake while searching for his European sweetheart, Nina, who is awaiting him in Haifa. Lolek becomes Mintz's subordinate on the hill, and a sadistic, even erotic power relationship develops between them. The plot's development gradually subverts the shallow contrast between the Diaspora Jew and the new Zionist Jew.

"It all begins with getting sunburned," says Rosenberg, born in Tel Aviv in 1979, in a joint interview with Tiran and Leon, describing the experience that prompted him to make the movie. "I never could get a suntan. The basic experience of those who burn versus all the tanned boys is one that sets you apart. On the army base, those who burn cannot be part of beautiful Israel - they can't be the poster boys of Zionism. Even if today some of the images that attract interest are of pale men, the basic desire to adopt the image of the Canaanite remains unchanged."

Rosenberg's inspiration for the movie came from a photograph of his grandfather, taken in 1948. "You see three soldiers standing beside a hill near an abandoned Arab house, wearing tattered uniforms and peering fearfully at the camera," he says. "On the other side there is a goat; on the roof stands a soldier, holding a rooster and smiling. I remember my grandfather's look, the disconnect and the contrast between the war ethos and the frightened look in his eyes."

"For someone who lived in Poland, coming to the desert is just about the same as landing on the moon," Tiran, best known for his role as Hamlet at the Cameri theater, explains. "It's something that, if you've never seen it before, you just can't imagine. Lolek asks Mintz what Arabs look like: Every person in the audience knows what Arabs look like, but for Lolek, he has landed on another planet. It's a world of ghosts."

The decision to have the heroes speak Yiddish required considerable effort on the part of all three. Rosenberg wrote the screenplay in Hebrew, studied Yiddish and translated the dialogue with the help of teachers, led by Yiddish translator Moshe Sacher.

Leon and Tiran studied for months so they could converse in authentic Lodzian Yiddish. "It was important to me to write in Lodzian Yiddish," Rosenberg says, "because the Yiddish spoken today is the more literary sort, and the Lodzian Yiddish spoken by millions in Eastern Europe is quickly dying out. It is a way of preserving the language, which is also juicier because it was spoken.

"The movie is about a struggle between several cultures," he continues. "It is about the erasure of Ashkenazi Judaism, so the decision to speak Yiddish is a significant one."

This is probably one of the only feature films made in Yiddish since World War II. Rosenberg was surprised to hear many people in the audience laugh at the Yiddish that the two heroes speak in the opening scenes, which are not comic: "It's interesting that people laugh at first," he says. "They think that if Itay Tiran and Miki Leon are speaking Yiddish, I must be laughing at something. Yiddish has become Hebrew's 'sidekick.'"

Haaretz Daily Newspaper, By Yotam Feldman, August, 2008

Homeland: 40 Minutes of BrillianceDani Rosenberg's film staring Itay Tiran as a Yiddish speaking Holocaust survivor is unlike any other Israeli film. It presents a Father Land that has no room for mothers.

There are very few films made in Yiddish these days. It seems useless to create dialogue in a language that has supposedly passed from this world…But I doubt that the limited audience possibilities are what motivated Dani Rosenberg to create one of the few Yiddish speaking films produced since World War II. Before the screening one could surmise that the use of Yiddish is a mere gimmick – but the film itself dispels any question marks and proves that it should only – and could only be made in Yiddish.

After all this is the story of Lolek (played by a pale Itay Tiran), a new immigrant who we first meet in total darkness as he is humming a tune whose refrain will become significant later on. The strong sun, which irritates the characters as well as the audience throughout the film, suddenly shines on what we see is the back of a vehicle. Lolek, it seems has been chosen to get off in the midst of a dessert no-where.

From there he makes his way to a remote and hot out-post whose commander is a tan and tough "Sabra" (Mikki Leon). As the two embark on a game of commander and private – a game whose outcome is unknown- the Sabra, the native Israeli is seen to be a Yiddish speaker with a number on his arm. While our friend the polite foreigner is learning how to become "blue and white" in the most militaristic way. He actually had only wanted to get to Haifa to meet the girl he loves, and maybe even a bit of shade.

The story of the film takes place in 1948 and was made as part of the director's final project at the Sam Spiegel Film School in 2006.

The most amazing part of this production is the Yiddish coming out of the actors' mouths. Tiran and Leon learned the language thoroughly over a period of two months…

The film has more to sell than just the wonderful performances by these two fine actors. By placing the story in the period of the War of Independence, it is possible to bring criticism of the military which is often blunt and blind, or to condemn the utter destruction that took place in order to build a new society for immigrants.

The whole thing of course has repercussions for our times. The name of the film is planted in a line that Leon says as he welcomes Tiran to the "land of our fathers" – which begs the question: what about the mothers? It seems that they, along with all emotions that show up here, will continue in the only role that war time will allow.

The 40 minute Homeland will be presented at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque. Don't worry about the length of the film – or shortness of it. It is time to give Israeli short films a chance so that those who created them will also be able, in the future, to give us their longer works which at this stage are still in developments.

www.mouse.co.il/ by Oron Shamir, August 20, 2008

Suntan Camp

The tanning sunlight can only help the Holocaust survivors. Not only does the suntan improve the pale, deathly look that characterizes them, but it has another advantage – it obscures the number tattooed on the arm of someone who came from There, from the camps. And what is more fitting for the new man, who is rehabilitating the wreck that is his life, than a strong arm, free of traumas?

Lolek, a 25-year Polish Jew who was there during the War, ends up in the Negev desert, not by choice, in the middle of the battles of Israel's War of Independence. He has absolutely no connection to the Zionists who bark orders at him in Hebrew, nor does he have any bonds connecting him to their goals. He only speaks Yiddish, and is looking for Nina, his beloved girlfriend, whom he hopes was saved from the European inferno and perhaps lives in Haifa.

Dani Rosenberg, the director of the drama, "Beit Avi" (Homeland) takes advantage of the point of departure described above, to create a strong film with political significance, which departs quite a bit from its cinematic context. Much has already been written about the immigrants torn from Europe who ended up here in 1948 and were sent straight from the ships to the battlefields in Latrun or the southern plain.

Rosenberg, a filmmaker at the beginning of his career, provides a very effective visual expression for this chapter in Israel's history. The film can certainly be placed in the post-Zionism niche.

Rosenberg, a graduate of the Sam Spiegel Film School, has already swept up not a few prizes for his short films ("The Red Toy", "Don Quixote in Jerusalem"), which he directed while still in school. The drama "Beit Avi", 40 minutes in length, is his final school project, and was first shown at the Jerusalem Film Festival. It displays young Rosenberg's attributes as a decisive film writer, as a designer of intensely expressive scenes, and as an excellent director of actors.

Itay Tiran (who corresponds interestingly here with the role he played in Udi Aloni's film "Forgiveness") is Lolek, who is not a firm believer in Zionism. Along with him, Miki Leon amazingly portrays the strict army commander, who also came from There, but who's tanned and healthy skin covers up his secrets and pains from the past.

The boldness of "Beit Avi" is also obvious from its unusual dialogue; it takes place entirely in Yiddish, which has always been perceived as the strongest contradiction to the Israeli ethos that sees its self as all-conquering and confident. Many sources contributed funds to producing "Beit Avi", particularly the Second Authority for Television and Radio. Nonetheless, somehow it is hard to believe that someone on Channel 2 will broadcast this painful film.

In Dani Rosenberg's new film, Itay Tiran plays a Yiddish Speaking Holocaust Survivor who is dropped off in the middle of the dessert

Dani Rosenberg's new film tells the story of Lolek, a young Holocaust survivor who arrives in Israel in 1948 and is recruited directly into the IDF and forced to defend a remote outpost in immediately upon his arrival. On this remote outpost he meets another soldier who forces him to recognize the bitter truth.

The film is entirely in Yiddish and it is one of the few films produced in that language since World War II. The two actors, Itay Tiran and Mikki Leon studied Yiddish for two months in preparation for the film.

In an interview with the Ha'aretz newspaper, director Dani Rosenberg explained that the inspiration for the film came from a photo of his grandfather where there are three soldiers standing near an old abandoned Arab house – their uniforms are crumbled and in their eyes there is fear. On the other side of the frame there is a goat and a soldier standing on the roof holding a chicken. He remembers his grandfather's look – the disconnect between the military ethos and the fear in his eyes.

Netta Alexander, August 20th 2008

http://www.mouse.co.il/CM.articles_item,636,209,26876,.aspxHomeless

Dani Rosenberg's "Homeland", which straddles the two worlds of the old Diaspora Jew and the new Israeli Sabra, is yet another example of a short and successful drama that gets lost on its way to a wider audience

Homeland, the short (40 minutes) and excellent new film by Dani Rosenberg is showing sporadically at a few cinemas right now. A few weeks ago the talented Nadav Lapid's 50 minute film "Emile's Girlfriend" was also shown at a few cinematheques around the country. That film won much praise in France where it was also shown commercially.

This is the sad story of Israeli short films – as praiseworthy as they might be- the films just fall between the cracks. On the one hand the length of the films seems ill-suited to a theatrical screening. On the other hand, as these two fine films will attest, their quality often exceeds that of full length feature films produced here.

Shmulik Duvdevani, Ynet, September 1st, 2008HOMELAND

Two new and unusual Israeli films portray the process that the Israeli soldier has undergone from victim to murderer

"Homeland" is a good example of this. Through the story of two Jewish Holocaust survivors, who roast out in the hot dessert sun as the War of Independence rages, Rosenberg tackles issues such as the artificial construct of the "Sabra", and the connection between Jewish and Arab refugees. …One of the characters (Itay Tiran) is a most recent immigrant who is actually trying to get to Haifa to find his girlfriend, and finds himself on a lonely hilltop in the middle of the dessert. The other (Mikki Leon) is waiting for him on that hilltop and has already become the Sabra. He is mustached, tan and muscular – yet underneath that he is hiding the Diaspora Jew that Zionism tried to exorcise. This surrealistic situation, which recalls Rafi Bukai's film "Avanti Popolo", becomes even more strange and encumbered by the fact that all the dialogue is in Yiddish.

The somewhat erotic, sadomasochistic relationship between the two- the pale weak Diaspora Jew and the tanned macho commander, express a concrete question about the ways in which, the Jew is attracted, in an almost Fascistic way, to power. The "discovery" of an abandoned Palestinian village by the character portrayed by Itay Tiran, who stumbles upon the body of a local boy, supplies the film with one of its most powerful moments and expresses the Holocaust survivor's attraction to death.

The element of violence that the new immigrant identifies with on his way to becoming a "new Jew" leads to a surrealistic departure scene in which the character says good bye to the old Diaspora world. All of a sudden, the timeless discussion of Jewish victimhood is seen in a different light. This is an issue that has been already presented by new historiography of Zionism, but not yet by the contemporary cinema. …

The History of Violence, Yair Raveh, Ynet, September 3rd, 2008Festivals

- Thalia Kino, Dresden, Germany, 2009

- Philadelphia Jewish Film Festival, USA, 2010

- Dresden Jewish Film & Music Week, Germany, 2009

- 4th Forum of Israeli Cinema in Russia, 2009

- Jewish Eye Film Festival, Ashkelon, Israel, 2009

- CinemSpace Montreal, Canada, 2009

- Film IsReal Festival, Amsterdam, 2009

- Eitzeit Kino, Berlin, Germany, 2009

- Brown Israeli Film Festival, Rhode Island, USA, 2009

- Israfest NY/Miami/LA Festival, USA, 2008

- Toronto Jewish Film Festival, Canada, 2008

- PALIC, Belgrade Film Festival, 2008

- Zurich Int'l Film Festival, Switzerland, 2008

- Cinematography Schools International Encounter, Mexico City, 2008

- Kolkata Film Festival, India, 2008

- The Jerusalem Film Festival, 2008

Educational

- Franklin & Marshall College

- University of Michigan

- US Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Johns Hopkins University

- University of Denver

- University of Texas at Austin

- Library of Congress

- Arizona State University

- University of Pennsylvania

- Duke University

- Harvard University

- Maryland University